See other History Articles

Title: Thomas J. DiLorenzo’s “The Real Lincoln” — a rebuttal

Source:

Hidden History

URL Source: http://hidhist.wordpress.com/lincol ... s-the-real-lincoln-a-rebuttal/

Published: Sep 1, 2010

Author: J. Fepperson

Post Date: 2010-09-01 17:42:29 by Original_Intent

Keywords: DiLorenzo, Lincoln, Civil, War

Views: 282

Comments: 9

Historical scholarship is often a controversial field, so it is no surprise that occasionally we find some argument or dissension over a book or article which appears. This web page is devoted to exposing what its publisher and contributors think are a number of grievous errors in Thomas DiLorenzo’s recent book on Abraham Lincoln (The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War; Prima Publishing [an imprint of Random House], 2002). Several people helped with the preparation of this site, and the publisher would like to especially thank Prof. Richard Ferrier of Thomas Aquinas College, and Col. A.T. Mackey, USAF. Any errors in the site are the publisher’s responsibility. If anyone has questions or comments about this web page, you are encouraged to email the publisher at jfepperson@aol.com. Any references in the first person are to the publisher of the site. About the website publisher. Links to other commentary on DiLorenzo’s book Summer, 2005, revision: In the late summer/fall of 2005, I made some major revisions to this site. The “categorization” of flaws was done away with, mostly because several readers pointed out that much of the categorization was arbitrary and capricious. Also, I was able to borrow a copy of DiLorenzo’s second edition, which did address some of the complaints made in the site. Finally, I tried to address some of the criticisms of the anonymous site, which defends DiLorenzo’s book (poorly, in my opinion) from my complaints. I’d like to thank Joseph Eros of Shepardstown, WV, for loaning me the second edition, and Col. Mackey for his help in preparing the revision. Any shortcomings in the revision are, of course, my responsibility. Summer, 2005, revision: In the late summer/fall of 2005, I made some major revisions to this site. The “categorization” of flaws was done away with, mostly because several readers pointed out that much of the categorization was arbitrary and capricious. Also, I was able to borrow a copy of DiLorenzo’s second edition, which did address some of the complaints made in the site. Finally, I tried to address some of the criticisms of the anonymous site, which defends DiLorenzo’s book (poorly, in my opinion) from my complaints. I’d like to thank Joseph Eros of Shepardstown, WV, for loaning me the second edition, and Col. Mackey for his help in preparing the revision. Any shortcomings in the revision are, of course, my responsibility. ——————————————————————————– Page 2: (First edition) “The [Civil War] created the highly centralized state that Americans labor under today.” (The second edition uses the same language.) Those of us familiar with the New Deal and the Great Society might take issue with this unsupported assertion, inasmuch as those periods of history saw much more (and more permanent) growth of the Federal government than did the Civil War era. Ditto for the Progressive Era. Page 3: (First edition) “Lincoln thought of himself as the heir to the Hamiltonian political tradition” (The second edition uses the same language.) This is another unsupported assertion (no footnote is given), and I conducted a brief experiment to see if Lincoln’s own words would back it up. I went to the Lincoln Papers online site and did a simple search on the word “Hamilton.” If DiLorenzo’s assertion were valid, it seems clear to me that I ought to get a lot of hits; I got a grand total of 26 hits, the first three of which were not to Alexander Hamilton! In fact, looking through the citations, only five of them referred to Alexander Hamilton; the rest were to locations named Hamilton or to Union officers named Hamilton. It seems to me that this is a sparse degree of citation for someone who thought of himself as Hamilton’s “heir.” It is true that there is an element of political lineage from Hamilton the Federalist through Clay the Whig to Lincoln the Whig and Republican, and there is no doubt that Lincoln thought highly of Clay — Lincoln probably did see himself somewhat as Clay’s heir — but if Lincoln saw himself as Hamilton’s political heir I think he would invoke Hamilton’s name more often. Page 4: (First edition) “It is very likely that most Americans, if they had been given the opportunity, would have gladly supported compensated emancipation as a means of ending slavery ” (The second edition uses the same language.) While this might well be true (although I personally doubt it), DiLorenzo provides no evidence that any of the slaveholding states would have accepted an offer of compensated emancipation. In 1862, Lincoln proposed compensated emancipation to the Congressional delegations from the (loyal) Border States; they rejected it. Why does DiLorenzo assume that the Deep South states would have accepted a similar offer? The extensive writings from leading Southerners in defense of slavery (see this website for a sampling) argues that they would not have voluntarily given it up. For example, Stephen Hale, Alabama’s commissioner to the state of Kentucky, writing to Governor Beriah Magoffin of that state, writes “African Slavery has not only become one of the fixed domestic institutions of the Southern States, but forms an important element of their political power, and constitutes the most valuable species of their property– worth, according to recent estimates, not less than four thousand millions of dollars; forming, in fact, the basis upon which rests the prosperity and wealth of most of these States, and supplying the commerce of the world with its richest freights, and furnishing the manufactories of two continents with the raw material, and their operatives with bread.” Later in the same letter Hale writes “What Southern man, be he slave-holder or non-slave-holder, can without indignation and horror contemplate the triumph of negro equality, and see his own sons and daughters, in the not distant future, associating with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality, and the white man stripped, by the Heaven-daring hand of fanaticism of that title to superiority over the black race which God himself has bestowed?” Similarly, William Harris, commissioner to the state of Georgia from Mississippi, said in a speech to the Georgia General Assembly “She [Mississippi] had rather see the last of her race, men, women and children, immolated in one common funeral pile [pyre], than see them subjected to the degradation of civil, political and social equality with the negro race.” Neither of these sounds like someone interested in emancipation of any kind, and there are many more similar expressions to be found. Finally, it should be pointed out, if any slave-owning state had wanted to offer a compensated emancipation plan on their own, they had all the authority they needed. I am unaware of any state offering such a plan. So where is the evidence that any slave state would have accepted such a plan? It seems to me that DiLorenzo is indulging in a rhetorical flourish to distract the reader from the uncomfortable fact that the Deep South states were very committed to slavery. Page 5: (First edition) “This doctrine [secession] was even taught to the cadets at West Point, including almost all of the top military commanders on both sides of the conflict” (The second edition uses the same language.) This is almost surely a reference to William Rawle’s treatise on the Constitution (A View of the Constitution of the United States, 1825), which was used as a text at West Point for one or two years in the mid-182082;s, and then replaced by a different book which did not, in fact, advocate the legality of secession. The claim that DiLorenzo makes was made often in the postwar era in publications such as the Southern Historical Society Papers, and was soundly refuted in an article published in The Century, vol. 78, no. 4, (Aug. 1909), pp. 629-635, written by Col. Edgar S. Dudley. Jefferson Davis furnishes some of the supporting evidence to refute the claim that Rawle was a text of long standing at the Academy (see the Southern Historical Society Papers [SHSP], vol. 22, p. 83). An extended discussion of this issue is in Douglas Southall Freeman’s biography of Lee, RE Lee, vol. 1, pp. 78-79, and Thomas Fleming’s West Point: The Men and Times of the United States Military Academy, West p. 59. Were some future Confederate leaders at West Point when this book was used? Absolutely; a partial list would include Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Joseph Johnston, and Leonidas K. Polk. But to say it was used by “almost all of the top military commanders on both sides” is to do violence to the truth. It wasn’t used when Grant or Sherman or Jackson or Stuart were at the Academy. Further, it needs to be pointed out that we do not even know if the material on secession was ever used. In Lee’s case, we know from his own correspondence that he did not accept Rawle’s views, for in January, 1861, he wrote to his son “Rooney” that “secession is nothing but revolution.” Besides, the fact that Rawle was replaced by Kent’s Commentaries (which does not support secession) undermines the implied claim that there is some endorsement of secession here. Finally, it needs to be said that there are no known instances of a secessionist claiming Rawle’s authority for their action in 1860-61 (some did claim it, many years after the fact; no one, that I’m aware of, made such a claim during the Secession Winter). A serious scholar would have discussed all of this. DiLorenzo, of course, does not, because he is more interested in furthering the impression that West Point somehow endorsed the idea of secession than he is in honest historical inquiry. Page 6: (First edition) “Chapter 7 details how Lincoln abandoned the generally accepted rules of war, which had just been codified by the Geneva Convention of 1863.” (The second edition uses the same language.) While quibbling about dates is perhaps unbecoming, there was no Geneva Convention of 1863. There was a Geneva Convention of 1864, but according to the Avalon Project website at Yale this involved only the treatment of wounded enemy soldiers (some broader protection is given to those who help the wounded). In other words, it wasn’t a complete codification of the “accepted rules of war,” which in fact were first formulated in the Union’s General Orders 100, known informally as the Lieber Code. For more detail the reader is referred to the article “The United States and the Development of the Laws of Land Warfare” by Capt. Grant R. Doty (U.S. Military Academy) in the journal Military Law Review, vol. 156, pp. 224-255, 1998. While the Union war effort was oftentimes harsh and did step over the bounds on a few occasions (usually due to the excesses of an individual commander, as opposed to established policy), DiLorenzo’s accusation cries out for some substantiating details, which are, of course, not given. The claims of the website also cry out for some substantiation, which is not given. Page 7: (First edition) “Chapter 9 describes Lincoln’s economic legacy: the realization of Henry Clay’s American System. Many (primarily) Southern statesmen had opposed this system for decades.” (The second edition uses the same language.) DiLorenzo conveniently ignores the many prominent Southern Whigs who favored Clay’s ideas (such as Alec Stephens, future Vice-President of the Confederacy) and the many Northern Democrats who did not. The point is that the debate over the American System did not split perfectly along North-South lines. By the time of the Civil War the divide was more North-South than it had been, but this was largely due to the importance of the slavery issue. Page 8: (First edition) “Lincoln’s war created the ‘military-industrial complex’ some ninety years before President Eisenhower coined the phrase.” (The second edition uses the same language.) While this appears to me to be an outlandish assertion which cries out for some kind of substantiation, DiLorenzo provides no footnote to support his claim. I, for one, find any comparison of the 187082;s era United States military-industrial “complex” with what existed beginning in the 195082;s to be unsupportable, although I confess it is the kind of negative assertion which it is difficult to prove. It is worth pointing out that Eisenhower was warning against a permanent establishment, which was not the case in the post-Civil War period, when the United States military shrank from a force of several million to something like 25,000. I’ll concede that DiLorenzo is perhaps indulging a rhetorical flourish here, but it is an outlandish and unsubstantiated one, in my opinion. Pages 10-32 DiLorenzo’s entire point in Chapter 2 is “Lincoln’s Opposition to Racial Equality.” Let’s hear what others had to say about Lincoln’s ideas along this line. During the senatorial debates in 1858, Stephen Douglas charged that Lincoln “objects to the Dred Scott decision because it does not put the Negro in the possession of the rights of citizenship on an equality with the white man.” Now it could well and truly be said that this was asserted in the midst of a political campaign, and it is the nature of politicians to frame their assertions so as to place their opponents in the worst possible light. Fair enough. But why does DiLorenzo then insist that each and every one of Lincoln’s statements — made to racially prejudiced Illinois audiences — be taken literally? Why is Lincoln not allowed to be a politician trying to walk the tightrope between what he believes and what the electorate believes? It might be instructive to hear what Frederick Douglass thought of Lincoln’s racial views: “In all my interviews with Mr. Lincoln, I was impressed with his entire freedom from popular prejudice against the colored race.” The fundamental point, which DiLorenzo ignores, is that Lincoln grew. During the 185082;s, he was as possessed of racist tendencies as any man in the United States. However, he still believed slavery was morally wrong, and by the end of the war his attitudes towards blacks had changed substantially. His very last public speech, just a few days before his death, contained language suggesting that some free blacks should be given the vote. Does DiLorenzo acknowledge this? Of course not. Page 15: “In twenty-three years of litigation [Lincoln] never defended a runaway slave, but he did defend a slaveowner.” The reference to defending a slaveowner is to the notorious Matson case, in which Lincoln represented (as an assistant) a Kentuckian who owned land in Illinois which he worked with the help of some slaves he brought over from Kentucky for part of the year. There is no denying that this case causes some embarassment to those who hold Lincoln in high esteem, but the fact is that Lincoln did defend a black woman, Nance, who was accused of being a slave (Bailey v. Cromwell, 4 Ill. 71 [1841]); strictly speaking, Lincoln did not represent Nance, he simply demonstrated that her alleged owner could not establish that she had ever been a slave, thus legally establishing her as a free person under Illinois law. While DiLorenzo’s assertion, “he never defended a runaway slave,” may be, strictly speaking, true, to omit the Nance case in this discussion is shoddy scholarship. Perhaps the best comment on this comes from Lincoln scholar David Herbert Donald: “Neither the Matson case nor the Cromwell case should be taken as an indication of Lincoln’s views on slavery; his business was law, not morality.” Page 17: (First edition) “Some ten years later, December 1, 1862, in a message to Congress, Lincoln reiterated his earlier assertions: ‘I cannot make it better known than it already is, that I strongly favor colonization.’” (The second edition uses the same language.) In a document dedicated to highlighting the flaws and inaccuracies of another’s work, it behooves me to own up to my own mistakes. Quite simply, my original comments on this point were inaccurate. Because of this, and because the anonymous website devotes so much space to its criticism of this point, I’ll make my correction in some detail. Lincoln apparently was still interested in colonization the summer after he wrote the above comments, for he discussed it with a delegation of free black pastors who visited the White House in 1863. However, by July 1st, 1864, his secretary, John Hay, was writing in his diary that Lincoln had “sloughed off” colonization, indicating that it was fading in its interest. In the meantime, a pilot effort had been launched in the Chiriqui region of Central America and another one on the island of Hispanola, in what is now Haiti. A detailed discussion of either of these ventures is simply not appropriate in this setting. The criticizing website refers to an account by Union general Benjamin Butler which suggests that, as late as April, 1865, Lincoln was still interested in colonization. Unfortunately for the anonymous website author, Mark Neely has demolished Butler’s credibility in an article in Civil War History (“Abraham Lincoln and black colonization: Ben Butler’s spurious testimony,” Civil War History, vol. 25, no. 1 (1979), pp. 77-83.). The short version is that Butler was making things up when he wrote his memoirs. DiLorenzo makes a big issue of Lincoln’s support for colonization, but he overlooks its disappearance from his agenda. A true scholar would not do that, but a political polemicist might. DiLorenzo (and many others) also ignores the fact that Lincoln was not the least bit interested in forcibly deporting people, but in allowing for voluntary emigration, not because he didn’t want blacks in the country, but because he feared for how the two groups (blacks and whites) would get along. A list of good scholarly articles on Lincoln and colonization follows: Paul Scheips, “Lincoln and the Chiriqui Colonization Project,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 37, no. 4 (1952), pp. 418-453. Gabor S. Boritt, “The Voyage to the Colony of Lincolnia,” Historian, vol. 37, no. 4 (1975), pp. 619-631. N. Andrew N. Cleven, “Some Plans for Colonizing Liberated Negro Slaves in Hispanic America,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 11, no. 1 (1926), pp. 35-49. An interesting site on Lincoln and colonization: http://www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org/content_inside.asp?ID=34&subjectID=3 Page 20: “Lincoln had no intention of doing anything about Southern slavery in 1860.” This is true as far as it goes, but it misses the point. Lincoln had spent the six years since his re-entry into politics in 1854 denouncing slavery as morally wrong. This is the theme of literally every speech he gave from 1854 to his election as president, and it was the theme of much of his private correspondence as well. In December of 1860, he would write to his old friend and fellow former Whig, Alec Stephens of Georgia, “You think slavery is right and should be extended; while we think slavery is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.” DiLorenzo also appears not to understand that, in the absence of a civil war, President Lincoln would have no authority to do very much about slavery in the South. It was only because of the rebellion that he could issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Page 24: (First edition) “The more or less ‘official’ interpretation of the cause of the War between the States, as described in The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, by historian William A. Degregorio, asserts that the slavery issue ‘pitted abolitionists in the North who viewed it as a moral evil to be eradicated everywhere as soon as practiable against southern extremists who fostered the spread of slavery into the territories.’” (The second edition uses the same language.) I, for one, have never heard of William A. Degregorio nor The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, and I would think that many better sources would exist for an “official” interpretation of the cause of the Civil War. This is nothing more than a strawman, and a weak one at that. No serious scholar takes this view of the Civil War, and while I do grant that many ordinary citizens might, that is an indictment of history education, not of Lincoln’s record. Page 25: (First edition) “No abolitionist was ever elected to any major political office in any Northern state.” Thaddeus Stevens (Congressman from Pennsylvania, 1848-1868), Salmon Chase (Governor [1856-1861] and Senator [1849-1855] from Ohio), and Charles Sumner (Senator from Massachusetts, 1851-1874) would be surprised to read this. While the definition of “abolitionist” might be a point of contention here, these three men — along with Ben Wade, Senator from Ohio — certainly held to extreme antislavery views. DiLorenzo’s second edition completely omits this claim, and wisely so. Page 26: (First edition) “[Lincoln] was thus the North’s candidate in the election…” (The second edition uses the same language.) Stephen A. Douglas would have been surprised to read this. Although Douglas did not do well in the Electoral vote, he is considered by many students of the 1860 campaign as the only candidate who could have won enough votes nationwide to defeat Lincoln. Page 32: DiLorenzo ends this chapter by saying, “The foregoing discussion calls into question the standard account that Northerners elected Lincoln in a fit of moral outrage spawned by their deep-seated concern for the welfare of black slaves in the deep South.” The problem is that this assertion is based on a false premise. I don’t think there is a “standard account that Northerners elected Lincoln in a fit of moral outrage…” This language is identical in both editions, and simply betrays DiLorenzo’s shallow knowledge of history. Allen Nevins makes a cogent point in this regard, however. “The nation had taken a mighty decision — the decision that slavery must be circumscribed and contained. Lincoln’s 1,866,000 followers wished to contain the institution by a flat Congressional refusal to recognize it outside; the 1,375,000 adherents of Douglas wished to contain it by local-option type of popular sovereignty.” Prologue to Civil War, pp. 316-317. Page 35: (First edition) “At the same time, it is important to note that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave.” (The second edition uses the same language.) This is simply absurd on its face, for the Emancipation Proclamation was the legal authority for the freeing of most of the slaves in the South. For example, all of the slaves in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, were freed under the authority of the Emancipation Proclamation; freedom perhaps did not come until the Union Army arrived, but once this happened the slaves in that area were free. Moreover, any slaves from these areas who had escaped to Union lines — and there were many in this category — would have been freed from bondage the instant the Proclamation went into effect. The fact is, while some Union-occupied parts of the Confederacy were exempted from the Proclamation (notably Tennessee, southeastern Louisiana, the new state of West Virginia, and eastern Virginia) some were not. Northern Virginia was not exempted, nor were northern Mississippi and Alabama, nor coastal North and South Carolina. Any slaves in these regions would have been freed as soon as the Proclamation was issued. A good article (with a nice map) is “After the Emancipation Proclamation,” by William C. Harris, North & South, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 42-53. The efforts of the anonymous website to defend DiLorenzo’s error seem tortured, to me. Page 37: (First edition) “The British writer Earl Russell noted …” (The second edition uses the same language.) Is this a mangled citation for the British Foreign Secretary Earl (as in a title of nobility) Russell? It’s a minor point, but for the author not to know this — and the way the passage is constructed he clearly does not seem to know this — is an unfortunate reflection on his knowledge of the period. The point is not that DiLorenzo identifies Russell as a writer — apparently he was one — but that he does not appear to know that Russell was the British Foreign Secretary during the Civil War years. Again, this is a minor point, but an accumulation of many such minor points makes for a major defect in the book. pp. 38-43: A large portion of Chapter 3 is devoted to a summary of the military history of the Civil War prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. This summary is extremely shallow and one-sided. The account of the Battle of Fredericksburg is particularly poor. The summary almost entirely emphasizes the so-called “eastern theatre” of the war, and almost completely ignores the “western theatre.” The reason for this is fairly obvious: DiLorenzo’s purpose here is to show that Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation out of desperation in the midst of losing the war. But DiLorenzo’s construction of the military history conveniently ignores almost all Federal successes, and minimizes those it does not ignore. Federal victories at Pea Ridge, Roanoke Island, Port Royal, New Orleans, and Corinth are ignored. The extent of the victories at Forts Henry and Donelson (12,000 Confederates prisoner, Nashville captured, most of Western Tennessee occupied) are minimized as “smaller battles.” Something DiLorenzo fails to notice, apparently, is that by the time the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the western Confederacy was shattered. Much of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana had been lost. The cities of New Orleans, Nashville, and Memphis had been lost. In the east, the Confederate capital of Richmond was constantly (if inexpertly) threatened, and a series of significant lodgements had been made along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. The importance to the Emancipation Proclamation of the battle at Antietam or Sharpsburg in September, 1862, is completely ignored. DiLorenzo did not make any changes in this section of the the second edition that I noticed. Page 38: (First edition) DiLorenzo puts the First Battle of Bull Run as occurring on July 16, 1861, instead of July 21. (The second edition uses the same language.) Again, this is a minor point, but it highlights DiLorenzo’s sparse knowledge of the historical context. The anonymous website’s effort to suggest that this date is not, in fact, an error, seems ridiculous. Page 44: (First edition) “An eyewitness to the [New York draft] riots was Colonel Arthur Fremantle, the British emissary to the Confederacy.” (The second edition uses the same language.) This creates the impression that Fremantle had some kind of official status, which he did not have. See Jay Luvaas’s book on the European view of the Civil War (The Military Legacy of the Civil War, University Press of Kansas, 1988 [orig. University of Chicago Press, 1959] p. 21). Again, this is a minor slip, but it should be apparent by now that the book has all too many such minor slips. At some point the “slips” become evidence of “sloppiness.” The point is not — as some claim — that Fremantle was or was not a colonel (he most certainly was), but that he was not (as DiLorenzo implied) any kind of official emissary from Great Britain. DiLorenzo should have known better than to suggest he was. The anonymous website again appears to miss the point. Page 45: (First edition) DiLorenzo states that the emancipation proclamation “caused a desertion crisis in the U.S. Army. At least 200,000 Federal soldiers deserted; another 120,000 evaded conscription; and at least 90,000 Northern men fled to Canada while thousands more hid out in the mountains of central Pennsylvania to place themselves beyond the reach of enrollment officers.” This statement is referenced to p. 67 of The Confederate War by Gary Gallagher. However, this is wrong in two ways. First, no such statements are to be found in Gallagher’s book, either on the page noted or anywhere else. (Gallagher’s book tends to focus only on the Confederate side of the war.) Second, DiLorenzo is blaming all desertions on the U.S. side of the Civil War on the Emancipation Proclamation — 200,000 is the consensus estimate for the total number of deserters throughout the war, according to Mark Weitz’s article on desertion in the Encyclopedia of the American Civil War (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2000). Needless to say, some Federals deserted before the proclamation was passed, so not all the desertions can be ascribed to it, and it seems unlikely that every U.S. soldier who deserted after September 1862 did so because of the proclamation. In the second edition the language in the text is the same, but the citation is changed to page 63 of James McPherson’s What They Fought For. That page does discuss the morale crisis which swept through the Federal armies in the winter of 1862-63, but it does not support DiLorenzo’s numbers. In addition, turning the page would bring the reader to the statement “In any case, the decline in morale proved short-lived,” along with some discussion showing that the entire issue is much more complex than DiLorenzo wants you to believe. Finally, the standard source on desertions in the Civil War is Ella Lonn’s book, Desertion during the Civil War, which DiLorenzo does not cite. Pages 54-84: DiLorenzo writes as if Lincoln’s embrace of tariffs were a greater betrayal of liberty than the Confederacy’s attempt to nullify the results of a free election and embrace of the “positive good” theory of slavery. Why does DiLorenzo concentrate his moral indignation on the man who emancipated slaves rather than on the Confederate leaders who fought to keep them on the plantation? There is a natural right of revolution but no legal or constitutional right of secession. If any state can leave the Union any time it wants, without first obtaining the consent of all the other parties to the compact, then there is no Union, only a temporary alliance of convenience. This, however, was not what the founders envisioned when they framed the Articles of Confederation (“perpetual union between the states”) and, later, the Constitution (“a more perfect union”). Page 68: (First edition) “In virtually every one of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln made it a point to champion the nationalization of money and to demonize Jackson and the Democrats for their opposition to it.” According to James McPherson writing in his book Battle Cry of Freedom (page 182), “Tariffs, banks, internal improvements, corruption, and other staples of American politics received not a word in these debates — the sole topic was slavery.” While a careful examination of the text of the debates — available online here — shows that Prof. McPherson is exaggerating a bit, the essential truth of his assessment holds up under scrutiny. By a large margin, race and slavery were the dominant topics of the debates; the issues of the bank and tariffs and monetary policy were marginal at best. In his second edition, DiLorenzo omits the direct reference to the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and instead says, “Lincoln frequently made it a point to champion the nationalization of money and to demonize Jackson and the Democrats for their opposition to it.” No footnote is given to point to any examples of this, of course. Pages 87-88: (First edition) DiLorenzo cites John Quincy Adams as supporting a right to secession in his 1839 Discourse, “The Jubilee of the Constitution,” pp 66-69. (The second edition makes the same point.) On page 68 of the Discourse, Adams writes, “In the calm hours of self-possession, the right of a state to nullify an act of Congress, is too absurd for argument, and too odious for discussion.. The right of a state to secede from the union is equally disowned by the principles of the Declaration of Independence.” Adams’s subsequent reference to a right of the people in the states to dissolve the political bands that had held them in union is explicitly compared by him to the revolution of 1776. But that makes it, not a legal right, but a natural, extra-legal right. In short, it is the right of revolution as found in Locke and acknowledged by nearly every American statesman from Jefferson to Lincoln, and measured, as Adams says, by “[t]he tie of conscience, binding them to the retributive justice of Heaven.” Since DiLorenzo apparently does not understand the distinction between legal and natural right, he completely misreads the whole speech. (The second edition uses the same language.) Pages 125-126: “Since they were so dependent on trade, by 1860 the Southern states were paying in excess of 80 percent of all tariffs…” (The second edition uses the same language.) There is no question that some prominent Southerners believed this, but it is difficult to reconcile that belief with the data. Stephen Wise’s book on blockade running (Lifeline of the Confederacy, University of South Carolina Press, 1988) gives a table of tariff amounts collected at some ports (page 228); according to these figures, the Northern ports of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia took in more than $40 million in tariff duties, while the Southern ports of New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, Savannah, Norfolk, and Richmond took in less than $3 million, total. While some of the import duties paid in the North would no doubt be on goods sold to Southerners, it is difficult to accept that enough of this happened to result in 80% of the tariff being paid by Southerners, given the customs house figures. Even if DiLorenzo’s intent was to characterize the effect on Southerners of paying higher prices for tariff-protected domestic goods, it is difficult to justify his claim. The burden of the tariff would have fallen almost completely on the consumers, and the North had many more consumers than did the South. Page 128: “To a very large extent, the secession of the Southern states in late 1860 and early 1861 was a culmination of the decades-long feud, beginning with the 1828 Tariff of Abominations, over the proper economic role of the central government.” (The second edition uses the same language.) The documentary record of the Secession Winter, and the arguments put forward by the secessionists themselves, argues against this claim. See, for example, the documents archived here. The anonymous website does not like my pointing to my own (award-winning) website of secession documents, and suggests that there is something fraudulent about my selection of material. Those familiar with the site know that I have never refused to include a document which reasonably bore on the causes of secession. As for the documents my critic suggested needed to be included, The J.L.M. Curry speech is on my site here. I will leave it to the reader to decide if Curry supports secession because of tariffs or concerns about slavery and “Black Republicans.” The Wigfall speech is not about tariffs as a reason for secession. The Clingman speech is not about secession at all, except that the absence of the Gulf states will lead to a revenue crisis. The Hunter speech is clearly anti-tariff, but I found nothing in it which connected his tariff opposition to any support for secession. My impression is he was simply speaking out against the Morrill Tariff bill. Caveat: This is an extremely long speech, and I confess to only skimming it; I may have missed something, and would appreciate being informed of that if it is true. Page 131: (First edition) “Even though the large majority of Americans, North and South, believed in a right of secession as of 1861…” (The second edition uses the same language.) DiLorenzo provides no basis for this statement, which is refuted by the fact that Lincoln had wide-spread support for the war effort. The several resolutions by Northern state legislatures condemning secession as treason or rebellion would also argue against this assertion. See the resolutions of New York, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. These legislative resolutions, which ought to reflect some degree of popular sentiment, would by themselves contradict DiLorenzo’s assertion about “a large majority” believing in a right of secession. One can also look at what might be called “more informed” opinions on the matter of secession. Washington: “To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a government for the whole is indispensable. No alliance, however strict, between the parts can be an adequate substitute; they must inevitably experience the infractions and interruptions which all alliances in all times have experienced.” This is taken from his Farewell Address; emphasis added. In 1799, a citizen of Westmoreland County, Virginia, published a pamphlet entitled Plain Truth, about some of the political issues of the day. Among many other things, this author wrote, “In point of right, no state can withdraw itself from the Union. In point of policy, no state ought to be permitted to do so.” While the authorship of this pamphlet is uncertain, it has been traditionally ascribed by experts in American antiquaria to Henry Lee, father of Robert E. Lee. Madison: “It is high time that the claim to secede at will should be put down by the public opinion; and I shall be glad to see the task commenced by someone who understands the subject.” Letter to N.P. Trist, Dec. 23, 1832; The Writings of James Madison, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910, v. 9, pp. 490-91. Andrew Jackson: “To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union, is to say that the United States are not a nation.” [Andrew Jackson, Proclamation on Nullification, 10 Dec 1832].h Buchanan: “In order to justify a resort to revolutionary resistance, the Federal Government must be guilty of ‘a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise’ of powers not granted by the Constitution. The late Presidential election, however, has been held in strict conformity with its express provisions. How, then, can the result justify a revolution to destroy this very Constitution? Reason, justice, a regard for the Constitution, all require that we shall wait for some overt and dangerous act on the part of the President elect before resorting to such a remedy.” (Taken from Buchanan’s Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December, 1860.) Page 144: “‘Under the protection of Federal bayonets,’ wrote David Donald, ‘New York went Republican by seven thousand votes’ in the 1864 presidential election.” DiLorenzo cites this passage to page 81 of David Donald’s collection of essays, Lincoln Reconsidered. In the third edition, the correct citation is to page 180, but this is yet another minor matter. It is clear from his context that DiLorenzo is suggesting that somehow these Federal troops influenced the outcome of the election in New York. Now perhaps they did, but is there a larger context which Prof. DiLorenzo has failed to mention? In fact, there is. During the fall of 1864, the Confederacy was active in fomenting and aiding numerous attempts to disrupt the election. Some of these efforts centered on New York City, whose mayor (Fernando Wood) was suspected of being sympathetic to the Southern cause. In fact, a team of saboteurs would attempt to set fires in several New York hotels some weeks after the election, an effort which was supposed to have been timed to coincide with and therefore disrupt the election. It was to prevent this kind of disruption that Federal troops were sent to New York around election day, and they had the desired effect, according to the postwar memoir of one of the arsonists (Confederate Operations in Canada and New York, by John W. Headley, pp. 268-270). But readers of DiLorenzo’s book would never learn any of this. Page 148: “Lincoln was not opposed to secession if it served his political purposes.” DiLorenzo then begins to discuss the formation of West Virginia, which is admittedly a controversial topic. Alas, he appears to be unfamiliar with the extensive literature on the subject. While there were some irregularities in the process by which West Virginia came into being, for the most part the Federal government followed established constitutional procedures and standards. The Constitution requires only the permission of the parent state government for a state to be partitioned (Article IV, Section 3). As it happened, the recognized government of Virginia, the so-called loyalist Pierpont government, agreed to the partition (the fact that the Pierpont government was mostly from the western Virginia counties would explain this). By what authority did the Federal government recognize the Pierpont government as the legitimate government of Virginia? By Supreme Court decision, as written by no less a figure than Chief Justice Roger Taney (Luther v. Borden [1842], which held that the determination of legitimacy of competing state governments was a task for the “political” branches of the government, i.e., Congress and the President). It should also be pointed out that Congress, with perfectly clear Constitutional authority, implicitly recognized the Pierpont government by seating its Senators and Representatives. Without question, there were some irregularities in the process, but most of these centered on the issue of which counties to include in the new state. See the article in North & South (“Montani Semper Liberi,” by Ed Steers, Jr., vol. 3, no. 2, January 2000) for a good overview, as well as the extensive discussion in James Randall’s Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln. It is instructive to note, as DiLorenzo does not, that Virginia did not contest the partition in court after the war, but only the inclusion of some specific counties (Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 US 39). Page 158: (First edition: Regarding the 1862 Santee Sioux uprising in Minnesota) “Three hundred and three Indians were sentenced to death, and Minnesota political authorities wanted to execute every one of them, something Lincoln feared might incite one or more of the European powers to offer assistance to the Confederacy, as they were hinting they might do.” (The second edition uses the same language.) I would really like to know what evidence there is that the Europeans threatened to aid the CSA because of US Indian policy. Certainly DiLorenzo points the reader to none. The fact that the executions happened months after the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued also weighs against the story. The conventional story is that Lincoln intervened to prevent the execution of all but the most culpable offenders among the Indians. Supposedly (David Donald’s Lincoln, page 394) he insisted on executing only those who had actually committed murder or rape, and he insisted that the telegraph operator be especially careful in transmitting the 38 Sioux names over the wire, since an error in tapping out the imperfectly anglicized names of the Indians in Morse Code could send the wrong man to the gallows. DiLorenzo, who cites Donald’s book when it suits him, omits the comment on pp. 394-395 that Minnesota Senator Alexander Ramsey, who had been Governor of the state at the time of the uprising, told Lincoln in 1864 that if he had hanged more Indians he would have carried the state by a larger majority. Lincoln’s response was, “I could not afford to hang men for votes.” Page 174: (First edition) “In 1863 an international convention met in Geneva, Switzerland, to codify rules of warfare that had been in existence for more than a century.” (The second edition uses the same language.) This is inaccurate on several levels. As noted earlier, there was no Geneva convention issued in 1863, not one that codified rules of warfare (except as they applied to wounded soldiers; this chapter of DiLorenzo’s book is titled “Waging War on Civilians”); of equal importance is that the entire concept of “the law of war” was very fluid at this time. The generally regarded authority was the work of the Swiss jurist Emmerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, published in 1758; a 19th century edition is available online. Page 175: (First edition) DiLorenzo correctly mentions Henry Halleck as the author of a book on international law, but characterizes this book as having “informed virtually all the top commanders in the Union army (and the Confederate army as well).” (The second edition uses the same language.) It appears to have escaped DiLorenzo’s radar screen that Halleck’s book was not published until 1861, and so could not have informed any of the “top commanders” in either army except as a reference work after the war started. DiLorenzo provides no evidence to support this possibility. The anonymous website’s suggestion that DiLorenzo was referring to wartime circulation in his initial statement seems weak. Page 184: (First edition) “Upon entering Jackson, Mississippi, in the spring of 1863, Sherman ordered a systematic bombardment of the town every five minutes, day and night.” (The second edition uses the same language.) Does DiLorenzo really mean to say that after he occupied the town, Sherman ordered it bombarded? This makes no sense at all. Checking through the Official Records, one finds that this bombardment occurred during Sherman’s expedition to Jackson after the fall of Vicksburg, and was in response to the fact that the Confederates were defending the town, i.e., it happened as part of the effort to take the town. See Sherman to Grant, OR, Ser. 1, vol. XXIV, pt. 2, pp. 524-525. In other words, the bombardment that so disturbs DiLorenzo was an ordinary act of war. Page 201: “Shortly before his death in 1870, General Robert E. Lee told former Texas Governor Fletcher Stockdale that, in light of how the Republican Party was treating the people of the South, he never would have surrendered at Appomattox, but would have died there with his men in one final battle. ‘Governor, if I had foreseen the use these people designed to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox Courthouse; no sir, not by me. Had I foreseen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in my right hand.’” (The second edition uses the same language.) This story is weak on several levels. Douglas Southall Freeman, the premier biographer of General Lee, does not accept it. DiLorenzo cites a book by Thomas Nelson Page as his source, but Freeman notes that the evidence for the incident is second-hand (to DiLorenzo’s source it might be third-hand) and says, “There is nothing in Lee’s own writings and nothing in direct quotation by first-hand witness that accords with such an expression on his part.” (R.E. Lee, vol. IV, p. 374). Page 203: DiLorenzo states that revisionist historians of Reconstruction “have been dominated by ‘Marxists of various degrees of orthodoxy’” and cites p.9 of Kenneth Stampp’s book The Era of Reconstruction: 1865-1877 as support. Let’s see what Stampp really says (the first sentence starts on page 8): “The revisionists are a curious lot who sometimes quarrel with each other as much as they quarrel with the disciples of Dunning. At various times they have counted in their ranks Marxists of various degrees of orthodoxy, Negroes seeking historical vindication, skeptical white Southerners, and latter-day northern abolitionists. But among them are numerous scholars who have the wisdom to know that the history of an age is seldom simple and clear-cut, seldom without its tragic aspects, seldom without its redeeming virtues.” I will leave it to the reader to decide if DiLorenzo’s comment accurately reflects the meaning of Stampp’s words. (The second edition uses significantly different language, and the anonymous website ignores this point entirely.) Stampp does in fact use the words “Marxists of various degrees of orthodoxy”, but he does not say that they have dominated the school; he lists them merely as one of several groups that have been lumped together as revisionists and points out that the revisionists have frequently disagreed with each other. Pages 200-232: It is fair to ask, in my opinion, why DiLorenzo spends an entire chapter (33 pages) of a book on Lincoln on the subject of Reconstruction, which occurred after Lincoln was dead. Apparently, DiLorenzo’s point (see page 211) is that Lincoln’s agenda and policies led to Reconstruction and so it is proper to consider it part of his legacy. This thesis founders on the very real fact — which DiLorenzo conveniently ignores — that Lincoln and the radical wing of the Republican Party disagreed about Reconstruction policy, to the extent that Lincoln’s “pocket veto” of the Wade-Davis bill was a serious issue in the 1864 election campaign. DiLorenzo, of course, does not mention the Wade-Davis bill at all. Poster Comment: Just thought I'd throw a couple of logs on the fire. I expect this to be contended - which is why I posted it. "Man's mind stretched to contain a new idea never returns to its former dimensions." ~ Oliver Wendell Holmes

Post Comment Private Reply Ignore Thread

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

#1. To: James Deffenbach, randge, abraxas, christine, Kamala, farmfriend, All (#0)

(((((Ping y'all)))))

"One of the least understood strategies of the world revolution now moving rapidly toward its goal is the use of mind control as a major means of obtaining the consent of the people who will be subjects of the New World Order." K.M. Heaton, The National Educator

"...In school we learned that the Civil War was fought over the slavery issue. Abraham Lincoln was a "hero" because he freed the slaves. Actually, as we discover, when he declared war on the southern states which decided to secede from the Union, old Abe violated the Constitution allegedly to "preserve the Union." The Civil War was in reality the War for Southern Independence - freedom from rigid economic controls by northern industrialists who influenced government - NOT an issue of slavery. Most importantly the War for Southern Independence expressed the inviolable right of the people to be self-governing. States which voluntarily "joined" the Union of States retained the power to withdraw if it was deemed necessary. Those who say otherwise are ignorant or liars..." Excerpt from The South Was Right (not the book by the same name which is excellent).

Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. He (Gordon Duff) also implies that forcibly removing Obama, a Constitution-hating, on-the-down-low, crackhead Communist, is an attack on America, Mom, and apple pie. I swear these military people are worse than useless. Just look around at the condition of the country and tell me if they have fulfilled their oaths to protect the nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. Why the South Was Right, the North Wrong by Doug Bandow, November 2000 THE VICTORS WRITE history books, and the dominant accounts of the Civil War reflect the victorious perspective: misguided Southerners sought to destroy democratic governance and preserve slavery. Led by the heroic Abraham Lincoln, Northerners responded by saving the Union and emancipating the slaves. And for leading his moral crusade, Lincoln is America’s greatest president, martyred in his hour of triumph. Charles Adams, best known for his books on taxation, takes aim at this history. His analysis of what more accurately would be called the War of Northern Aggression is a bit different: With the passing of time, all wars seem pointless. The American Civil War certainly looks that way at this time in history. Heroes begin to look like fools. The glorious dead, the young soldiers who suffered and died, need to be pitied, and the leaders who led them to early graves need to be lynched. In that war, as in so many wars, the wrong people died. When in the Course of Human Events offers a sustained challenge to much of the conventional wisdom about the conflict. Indeed, the book’s title is a bit misleading. Adams doesn’t so much develop a comprehensive argument for secession as puncture the worst hypocrisies surrounding the North’s decision to initiate war. Observes Adams: “Lincoln’s concern that government ‘of the people’ would perish from the earth if the North lost may have been the biggest absurdity of all.” Particularly valuable is Adams’s critique of Lincoln. The victors’ history books tend to glide by Lincoln’s constitutional usurpations and violations. Adams does not. Even those familiar with the 16th president’s unconstitutional militia call, suspension of habeas corpus, and other lawless acts may not know that Lincoln ordered the arrest of U.S. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney for ruling that Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus without congressional approval violated the law. Only the failure of a U.S. marshal to carry out the order “saved the president from what would have been his worst crime against the constitutional scheme of government,” the author writes. The tariff and the war Adams’s most detailed argument, with interesting citations to domestic and foreign opinion of the time, is that the federal tariff was more responsible than slavery for the war. Certainly the tariff was a factor in the North’s decision to use force to prevent the South from leaving. Abolition was not particularly important: as Adams details, most Northern states shared the racism of the South, and several refused to allow free blacks to enter. Concern over the effects of lost revenue — the tariff was the federal government’s most important tax — and creation of a veritable free-trade zone in the South stoked Northern opposition to secession. Still, protectionism alone might not have been enough to justify a Northern invasion. Raw nationalism and anger over the South’s decision to pick up its marbles and go home also were important. Taken together, the combination proved irresistible, especially when most war hawks thought that little fighting would be necessary to reunite the states. This fatal underestimation of the costs of war, by both sides, might have been the decisive factor in leading the Southern states to secede and the Northern states to try to stop them. Adams’s emphasis on the tariff is less satisfactory when applied to the departing states. Although the protective tariffs passed at the behest of Northern manufacturing interests rankled Southerners, Lincoln’s election did not dramatically impact that issue. The rush out of the Union by the seven Deep South states reflected anger over the triumph of someone viewed as hostile to the South and fundamental fears about the security of the “peculiar institution.” Adams argues that the institution of slavery had never been more secure — but sometimes even otherwise rational people act irrationally. Indeed, the slave states could fear the continuing effectiveness of paper guarantees, especially if Lincoln used federal institutions to campaign against slavery. Not one to shy from controversy, Adams charges Northern generals with barbarism and war crimes. He contends that the actions of the Ku Klux Klan after the war — before its later lawless campaign against helpless blacks — could be understood in the context of defending Southern society from “the Yankee invaders” during Reconstruction. Finally, Adams offers a wonderfully vicious parsing of Lincoln’s celebrated Gettysburg Address. It might be “good poetry,” Adams writes, but that didn’t make it “good thinking,” based as it was on “a number of errors and falsehoods.” Standard histories of the War between the States make an inviting target for debunking. Adams joyously shoots away. Most of his criticisms hit home, but you don’t have to agree with all of them to recognize that he is right in calling the Civil War “a great national tragedy in every conceivable way,” including “a botched emancipation; the extermination of a whole generation of young men, including hundreds of thousands of teenage boys; the destruction of the constitutional scheme of limited federal power.” It is a war that should never have been fought. Mr. Bandow, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, is the author and editor of several books. This article originally appeared in the May 27, 2000, Washington Times.

Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. He (Gordon Duff) also implies that forcibly removing Obama, a Constitution-hating, on-the-down-low, crackhead Communist, is an attack on America, Mom, and apple pie. I swear these military people are worse than useless. Just look around at the condition of the country and tell me if they have fulfilled their oaths to protect the nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. And one more post about this to plug one of the best books that has ever been written about it (The South Was Right by the Kennedy Brothers). This review is from: South Was Right!, The (Hardcover) After purchasing the book through Amazon.Com and reading it, I could only wonder how many of the other reviewers had done the same! Yes, the authors refer to pro-union persons as Yankees frequently. I wonder if anyone has ever noticed how offensive the term "rebel" can be when used ad nauseam in a work? The authors do not use the term yankee with the vitriole other reviewers would have one believe but rather to call attention to the fact how desensitized our culture has become to the overly casual use of the terms "rebel" and "Civil War". Secessionist? Definitely. War for Southern Independence? Without a doubt. However, it will be odd to the enlightened observer that our culture commonly uses the term "rebel" as a perjorative, yet is offended by the same use of the collective "yankee". Truth be told, the war was not a Civil War, had it been, both armies would have fought for control of a central government. This was a war of secession, one nation (The Confederate States) seeking to remove itself from a seperate, sovereign nation just as the colonies had done with England and King George ninety years before. The authors point out with authority and documentation that the Constitution of The Confederate States of America forbade the further importation of slaves. The authors further document and narrate that the majority of slaves were not beaten and ill treated by slave owners as others would have one believe and that, all things considered, slavery was not the primary cause behind the war, as race relations were, if anything, more strained in the north than they were in the south. The authors do a good job underscoring the fact that they are not pro-slavery nor do they advocate a return to such a system. They do, however, show that the South in 1861 had evolved into a seperate economy and culture than that of the North, BOTH of which would later have to come to terms with the spectre of slavery. En toto, the authors show that the Confederacy was acting as a sovereign nation, in the tradition of their grandfathers, seeking to preserve personal liberty and the right to govern themselves as they best saw fit. The book is a must read for anyone who wishes an understanding not only of the motivation of the Confederacy but also of how we have come to have the all-powerful Federal governemnt running (nearly) unchecked in Washington today. Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. He (Gordon Duff) also implies that forcibly removing Obama, a Constitution-hating, on-the-down-low, crackhead Communist, is an attack on America, Mom, and apple pie. I swear these military people are worse than useless. Just look around at the condition of the country and tell me if they have fulfilled their oaths to protect the nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. Having read last night the Declarations of Secession for S.C., Texas, and Mississippi I think I have changed my view a little bit. Ultimately a lot of the impetus was coming from mercantilisitic and protectionist policies favoring northern industrialists, and upon that you will get no dispute. However, I was struck by the language in the Bills of Secession. Over, and over, and over the topic of slavery lies at the core of each. The adamant refusal of wealthy Southern Slave Holders to change their way of life and their insistence that they had a God given right to own other men as chattels merely because of the color of their skin. I know I live in a glass house as my ancestors were one of the largest slave holders in their area of North Carolina. However, one cannot avoid the issue of slavery if one but reads the documents in their own words. As well is the element of the Rothschild influence. I don't know as much of it as I would like, but from my reading Lincoln was aware of the presence of large numbers of British/Rothschild Agents seeking to drive a wedge between North and South and to thus cause the sundering of the Union. And to that Third Party agitation I lay much of the hidden cause of the War. I do agree it is a war that should never have been fought and that the causes which drove it were primarily the interests of a powerful few in both North AND South. I still don't think we have yet seen a complete and honest appraisal of the causes of the war. I do know popular sentiment of the time was against secession, and that regardless of the attempts to keep it that the practice of slavery had but a short time left regardless. I do agree with the reference that you refer to in "The South Was Right" that this was a clash of diverging cultures. It was one driven by custom, practice, and climate. The colder climate of the north was thus more conducive to heavy industry and less conducive to farming and vice versa. I must admit that I still love a warm Southern Night.

"One of the least understood strategies of the world revolution now moving rapidly toward its goal is the use of mind control as a major means of obtaining the consent of the people who will be subjects of the New World Order." K.M. Heaton, The National Educator

To me it always boils down to the same issue--did the states have the right to secede or not? I think they did. If they had a right to join together to form a union it would seem that they had no less right to decide that it was not in their best interest (for whatever reason) and to dissolve the tie/bond. People have the right to do that when government becomes oppressive so why wouldn't the states, which after all is a political fiction and is comprised of people. I will never accept the idea that once you become a party to a contract, a contract not between you and God but just other people, that you can't rescind it and stop participating in it if you decide it is no longer in your interest.

Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. He (Gordon Duff) also implies that forcibly removing Obama, a Constitution-hating, on-the-down-low, crackhead Communist, is an attack on America, Mom, and apple pie. I swear these military people are worse than useless. Just look around at the condition of the country and tell me if they have fulfilled their oaths to protect the nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. I think there the argument turns upon the following: Did, the several States, surrender their autonomy as separate and distinct political entities, i.e., nations by joining the Federal Union? The foregoing is a separate issue from the Tenth Amendment which reserves to the States and the People respectively all powers not granted to the Federal Government. What the question highlights is did the states retain the right of secession once entering into an open ended contract with the other states? If one answers yes then secession has a legal foundation and is not a rebellion against the senior authority of the Federal Union. If one views it as a binding open ended contract with no date of expiration then the right of secession is not retained and thus secession however cloaked was a violation of the contract and rebellion against an acknowledged senior authority - just as the American Revolution was a rebellion against the Crown.

"One of the least understood strategies of the world revolution now moving rapidly toward its goal is the use of mind control as a major means of obtaining the consent of the people who will be subjects of the New World Order." K.M. Heaton, The National Educator

Why would any man, or group of men, presumed to be sane, give up a right to disassociate when conditions become intolerable? To believe they would give up a right like that would be to believe them insane. "Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up, and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. This is a most valuable - a most sacred right - a right, which we hope and believe, is to liberate the world." Abraham Lincoln Of course he didn't believe that when the people in the south had had enough of the North and of him and decided they wanted to form a new government or to at least get rid of some dead weight.

Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. He (Gordon Duff) also implies that forcibly removing Obama, a Constitution-hating, on-the-down-low, crackhead Communist, is an attack on America, Mom, and apple pie. I swear these military people are worse than useless. Just look around at the condition of the country and tell me if they have fulfilled their oaths to protect the nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. Thank you, Abraham Lincoln, for leading America to "beat whitey" night at the Iowa state fair. You son-of-a-bitch. __________________________________________________________

#2. To: Original_Intent (#1)

Lord Acton

OsamaBinGoldstein posted on 2010-05-25 9:39:59 ET (2 images) Reply Trace

#3. To: All (#2)

Lord Acton

OsamaBinGoldstein posted on 2010-05-25 9:39:59 ET (2 images) Reply Trace

#4. To: Original_Intent (#0)

Lord Acton

OsamaBinGoldstein posted on 2010-05-25 9:39:59 ET (2 images) Reply Trace

#5. To: James Deffenbach (#2)

(Edited)

#6. To: Original_Intent (#5)

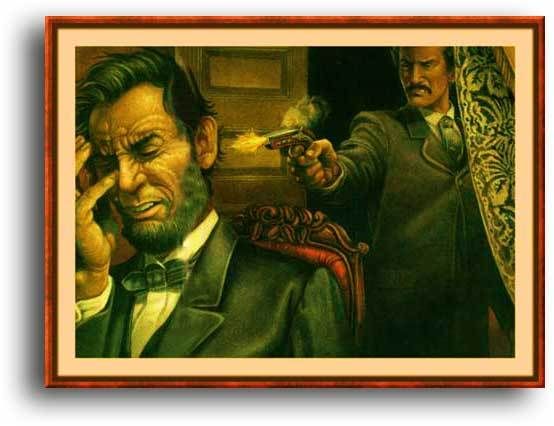

Lord Acton

OsamaBinGoldstein posted on 2010-05-25 9:39:59 ET (2 images) Reply Trace

#7. To: James Deffenbach (#6)

#8. To: Original_Intent (#7)

What the question highlights is did the states retain the right of secession once entering into an open ended contract with the other states? If one answers yes then secession has a legal foundation and is not a rebellion against the senior authority of the Federal Union.

Lord Acton

OsamaBinGoldstein posted on 2010-05-25 9:39:59 ET (2 images) Reply Trace

#9. To: Original_Intent (#0)

“What Southern man, be he slave-holder or non-slave-holder, can without indignation and horror contemplate the triumph of negro equality, and see his own sons and daughters, in the not distant future, associating with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality, and the white man stripped, by the Heaven-daring hand of fanaticism of that title to superiority over the black race which God himself has bestowed?”

"This man is Jesus,” shouted one man, spilling his Guinness as Barack Obama began his inaugural address. “When will he come to Kenya to save us?"

-Schweizerische Schuetzenzeitung (Swiss Shooting Federation) April, 1941

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest