(Originally published at Age of Autism, via The Daily Coin)

On September 23, 2014, an Italian court in Milan award compensation to a boy for vaccine-induced autism. (See the Italian document here.) A childhood vaccine against six childhood diseases caused the boy’s permanent autism and brain damage.

While the Italian press has devoted considerable attention to this decision and its public health implications, the U.S. press has been silent.

Italy’s National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program

Like the U.S., Italy has a national vaccine injury compensation program to give some financial support to those people who are injured by compulsory and recommended vaccinations. The Italian infant plaintiff received three doses of GlaxoSmithKline’s Infanrix Hexa, a hexavalent vaccine administered in the first year of life. These doses occurred from March to October 2006. The vaccine is to protect children from polio, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B, pertussis and Haemophilus influenza type B. In addition to these antigens, however, the vaccine then contained thimerosal, the mercury-containing preservative, aluminum, an adjuvant, as well as other toxic ingredients. The child regressed into autism shortly after receiving the three doses.

When the parents presented their claim for compensation first to the Ministry of Health, as they were required to do, the Ministry rejected it. Therefore, the family sued the Ministry in a court of general jurisdiction, an option which does not exist in the same form in the U.S.

Court Decision: Mercury and Aluminum in Vaccine Caused Autism

Based on expert medical testimony, the court concluded that the child more likely than not suffered autism and brain damage because of the neurotoxic mercury, aluminum and his particular susceptibility from a genetic mutation. The Court also noted that Infanrix Hexa contained thimerosal, now banned in Italy because of its neurotoxicity, “in concentrations greatly exceeding the maximum recommended levels for infants weighing only a few kilograms.”

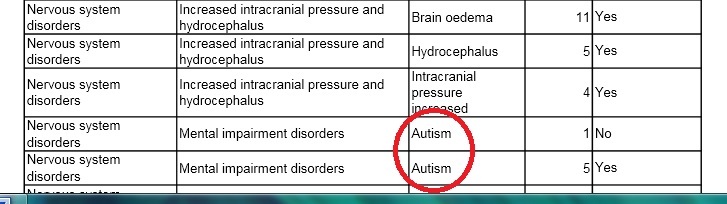

Presiding Judge Nicola Di Leo considered another piece of damning evidence: a 1271-page confidential GlaxoSmithKline report (now available on the Internet). This industry document provided ample evidence of adverse events from the vaccine, including five known cases of autism resulting from the vaccine’s administration during its clinical trials (see table at page 626, excerpt below).

Italian Government, Not Vaccine Maker, Pays for Vaccine Damages

As in many other developed countries, government, not industry, compensates families in the event of vaccine injury. Thus GSK’s apparent lack of concern for the vaccine’s adverse effects is notable and perhaps not surprising.

In the final assessment, the report states that:

“[t]he benefit/risk profile of Infanrix hexa continues to be favourable,” despite GSK’s acknowledgement that the vaccine causes side effects including “anaemia haemolytic autoimmune,thrombocytopenia, thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, haemolytic anemia, cyanosis, injection site nodule, abcess and injection site abscess, Kawasaki’s disease, important neurological events (including encephalitis and encephalopathy), Henoch-Schonlein purpura, petechiae, purpura, haematochezia, allergic reactions (including anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions),” and death (see page 9).

The Milan decision is sober, informed and well-reasoned. The Ministry of Health has stated that it has appealed the Court’s decision, but that appeal will likely take several years, and its outcome is uncertain.

Rimini: 2012 – Italian Court Rules MMR Vaccine Caused Autism

Two years earlier, on May 23, 2012, Judge Lucio Ardigo of an Italian court in Rimini presided over a similar judgment, finding that a different vaccine, the Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine (MMR), had caused a child’s autism. As in the Milan case, the Ministry of Health’s compensation program had denied compensation to the family, yet after a presentation of medical evidence, a court granted compensation. There, too, the Italian press covered the story; the U.S. press did not.

In that case, a 15-month old boy received his MMR vaccine on March 26, 2004. He then immediately developed bowel and eating problems and received an autism diagnosis with cognitive delay within a year. The court found that the boy had “been damaged by irreversible complications due to vaccination (with trivalent MMR).” The decision flew in the face of the conventional mainstream medical wisdom that an MMR-autism link has been “debunked.”

Italian Court Decisions Break New Ground in Debate Over Vaccines and Autism

Both these Italian court decisions break new ground in the roiling debate over vaccines and autism. These courts, like all courts, are intended to function as impartial, unbiased decision makers.

The courts’ decisions are striking because they not only find a vaccine-autism causal link, but they also overrule the decisions of Italy’s Ministry of Health. And taken together, the court decisions found that both the MMR and a hexavalent thimerosal- and aluminum-containing vaccine can trigger autism.

Italian Court Rulings Contradict Special U.S. Vaccine Court

These court decisions flatly contradict the decisions from the so-called U.S. vaccine court, the Court of Federal Claim’s Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. There, from 2007 to 2010, in the Omnibus Autism Proceeding, three decision makers, called Special Masters, found that vaccines did not cause autism in any of the six test cases, and one Special Master even went so far as to compare the theory of vaccine-induced autism to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

The Italian court decisions contrast starkly with these U.S. cases based on similar claims.

Read the full story at Age of Autism.

About the Author

Mary Holland is Research Scholar and Director of the Graduate Legal Skills Program at NYU Law School. She has published articles on vaccine law and policy, and is the co-editor of Vaccine Epidemic: How Corporate Greed, Biased Science and Coercive Government Threaten Our Human Rights, Our Health and Our Children (Skyhorse Publishing, 2012).