- The Guardian,

- Thursday March 6 2008

- Article history

on Thursday March 06 2008 on p1 of the Top stories section. It was last updated at 00:07 on March 06 2008.

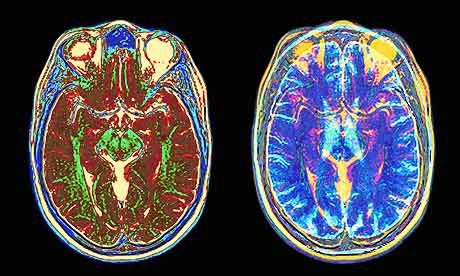

MRI scans

Scientists have developed a computerised mind-reading technique which lets them accurately predict the images that people are looking at by using scanners to study brain activity.

The breakthrough by American scientists took MRI scanning equipment normally used in hospital diagnosis to observe patterns of brain activity when a subject examined a range of black and white photographs. Then a computer was able to correctly predict in nine out of 10 cases which image people were focused on. Guesswork would have been accurate only eight times in every 1,000 attempts.

The study raises the possibility in the future of the technology being harnessed to visualise scenes from a person's dreams or memory.

Writing in the journal Nature, the scientists, led by Dr Jack Gallant from the University of California at Berkeley, said: "Our results suggest that it may soon be possible to reconstruct a picture of a person's visual experience from measurements of brain activity alone. Imagine a general brain-reading device that could reconstruct a picture of a person's visual experience at any moment in time."

It will inevitably also raise fears that a suspect's brain could be interrogated against their will, raising the nightmarish possibility of interrogation for "thought crimes". The researchers say this is currently firmly in the realm of science fiction because the technique can only be applied to visual images and, to date, the experiments rely on cumbersome MRI scanning equipment and extremely powerful magnets. The software decoder itself has to be adapted to each individual during hours of training while in the scanner.

However the team have warned about potential privacy issues in the future when scanning techniques improve. "It is possible that decoding brain activity could have serious ethical and privacy implications downstream in, say, the 30 to 50-year time frame," said Prof Gallant. "[We] believe strongly that no one should be subjected to any form of brain-reading process involuntarily, covertly, or without complete informed consent."

The technique relies on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a standard technique that creates images of brain activity based on changes in blood flow to different brain regions. The first step is to train the software decoder by scanning a subject's visual cortex while they view thousands of images over five hours. This teaches the decoder how that person's brain codes visual information. The next stage is to take a new set of images and use the decoder to predict the brain activity it would expect if the subject was viewing each of them. Finally, the subject views images from this second set while in the scanner. "We simply look through the list of predicted activities to see which one is most similar to the observed activity, and that's our guess," said Gallant.

The software matched their observed brain activity with the predicted activity from the decoder. When using a set of 120 images, the software got it right nine out of 10 times. With 1,000 images, the accuracy was eight out of 10. For 120 images, if the software were to simply make random predictions, its success rate would be just 0.8%.

The team estimate that if they used 1bn images (roughly the number on Google) it would have a success rate of 20%. With that many images, Gallant said, the software is close to doing true image reconstruction - working out what you are seeing from scratch. "There is no reason we shouldn't be able to solve this problem ... That's what we are working on now."

Gallant said it might be possible in future to apply the technology to visual memories or dreams. "Probably the visual hardware is engaged and stuff from memory is sort of downloaded into your visual hardware and then replayed," he said. "To the extent that that is true, we should be able to reconstruct imagery in dreams."

However, tests using moving images are not possible because MRI scanners are only able to take a new scan every three to four seconds. Other scientists say the advance should be welcomed as a major leap in understanding brain function.

"I think it's a significant advance," said Prof Marcel Just, a psychologist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. "It's much more exciting than mind reading and police interrogation ... These people are finding how the brain codes naturalistic scenes. They understand what the brain is saying."

"It's definitely an impressive result. It's pushing still further on how we can make inferences about mental states from looking at fMRI activity," said neurologist Dr Steven Laureys at the University of Liège in Belgium. He said the technique could be useful for understanding the mental state of a person who is in a coma.